THE ONLINE REGULATION SERIES 2021 | NEW ZEALAND

Online counterterrorism efforts in New Zealand have been shaped by the tragedy of the far-right terrorist attack on the Christchurch Mosque in March 2019 which killed 51 people, injured 40 others, and, critically, was livestreamed on Facebook. In the aftermath of the attack, New Zealand and France launched the Christchurch Call to Action in Paris on 15 May 2019 with the ambition of soliciting “a commitment by Government and tech companies to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online”.[1] Following the Christchurch Call, Prime Minister Jacinda Arden publicly announced a change in New Zealand’s existing legislative provisions concerning online harms and prohibited content, given that gaps in the country’s legal responses to terrorist and violent extremist content had been highlighted by the Christchurch attack. This led to the adoption of the Urgent Interim Classification of Publications and Prevention of Online Harm[2] in November 2021. The 2021 amendment most notably includes provisions related to livestreams.

Regulatory framework:

- New Zealand’s counterterrorism legislation includes the Terrorism Suppression Act

of 2002, the Search

and Surveillance Act, and 2012 the Terrorism Suppression

(Control Orders) Act, 2019. None of the above Acts include provisions specific to terrorist use of the

internet. - The

Counter-Terrorism Legislation Act, passed in October 2021. This legislation amends the existing

Terrorism Suppression Act. Amongst other provisions, the Act provides an updated definition of a ‘terrorist act’

and criminalises the preparation and planning of such acts. The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Act is based on

the recommendations of the Royal Commission of Inquiry

into the Christchurch Attack, and is said to have been fast-tracked by the September 2021 Islamic

State-inspired attack at an Auckland

Supermarket .[3] - The Harmful Digital

Communications Act (HDCA) of 2015 criminalises online content posted with the intention to cause harm. The

HDCA’s assigns liability to the individual posting the online content rather than on online platforms, which are

granted safe harbour protection if in compliance with the provisions of HDCA but with the exception of

“objectionable” content.[4] - The

Film, Videos and Publications Classifications Act, 1993 – known as the Classification Act, sets out the

criteria for classifying unrestricted, restricted, and “objectionable” (prohibited) content in New Zealand. The

Classification Act covers online content accessible in New Zealand and can be used by the Chief Censor – see

below – to request platforms to remove terrorist content. - The Urgent Interim

Classification of Publications and Prevention of

Online Harm Act, amending the Classification Act, November 2021.[5] In June 2021,

Jan Tinetti, Minister of Internal Affairs announced a

revision of New Zealand’s content regulation system to better protect New Zealanders from “harmful or illegal

content”. In amending the Classification act, the Amendment’s stated objective is “the urgent prevention and

mitigation of harms by objectionable publications” – with “objectionable publications” referring to

content that is prohibited under New Zealand’s Classification Act. In practice, this Amendment expands the scope

of the Classification Act to cover livestreamed content and to allow judicial authorities in New Zealand to

issue fines to non-compliant platforms.

Relevant national bodies:

- Classification Office (Office of Film and Literature

Classification): The Classification Office is in charge of content classification in New Zealand as provided

for by the Classification Act. - In December 2020, the Classification Office submitted a briefing to

Jan Tinetti on the challenges of the digital age, including: terrorist and violent extremist content and use of

the internet; mis/disinformation on social media; platforms’ algorithms and harmful “echo chamber”. - In the same briefing, the Classification Office outlines what New Zealand “needs” to face those challenges:

1. “A first-principles review of media regulation” to meet the needs of the digital age and facilitate

cross-sector engagement; 2. An “integrated strategy for violent extremism and dangerous disinformation online”. - Department of Internal Affairs (DIA):

The DIA manages Inspectors of Publications whose duties include submitting publications to the Classification

Office and monitoring the Classification Office on behalf of the Minister of Internal Affairs. - The Digital Safety Team of the DIA is in charge of “keeping New Zealanders safe from online harm by responding

to and preventing the spread of objectionable material that promotes or encourages violent extremism.” - The DIA leads on the Online Crisis Response Process to facilitate the coordination of any such response, such as

the Christchurch livestream, and the sharing of information between New Zealand governments, online platforms,

and civil society. The Process was developed through the Christchurch

Call Crisis Response Protocol, the EU Crisis

Protocol and the GIFCT Content Incident

Protocol. - Anyone can report violent extremist content to the DIA via the dedicated “Digital Violent Extremism Form”.[6] The form allows for the reporting of any type of content promoting

terrorism or encouraging violence, as well as reporting of terrorist operated websites, videos of terrorist

attacks, and any other content promoting violent extremism. All reports are reviewed by a DIA Inspector who can

work with the hosting platform to remove content (including to report violations of a platform’s content

standards); as well submit the content for classification by the Classification Office. The inspector can also

engage with relevant law enforcement, regulatory bodies, and online services overseas to ensure unlawful content

cannot be accessed from New Zealand.

Other organisations of relevance:

- NetSafe, an online safety non-profit

organisation supported by the Ministries of Justice and Education. On 2 December 2021, NetSafe published the Draft Aotearoa New Zealand Code of Practice for Online

Safety and Harms, drafted in collaboration with leading tech platforms (including all GIFCT founding

members and TikTok):[7] - The Code “brings industry together under a set of principles and commitments to provide a best practice

self-regulatory framework designed to enhance the community’s safety and reduce harmful content online.” - The Code creates an Administrator role, with the power to sanction signatories who fail to meet their

commitments, as well as a public complaint mechanism and a regular review process.

Key takeaways for tech companies:

Urgent Interim Classification of Publication and Prevention of Online Harm Amendment, 2021

- This Amendment is New Zealand’s policy response to the 2019 Christchurch Attack which, according to

policymakers, showed the limits of the existing Classification Act: - The livestreaming of objectionable content was not explicitly an offence under the Classification Act;

- The DIA did not have an explicit power to request platforms to remove objectionable content from their services,

or to enforce these requests; - The Act did not provide statutory authority for blocking objectionable content online, and there was no specific

offence of non-compliance with the Act when it related to online content; - The safe harbour protection provided in the HDCA overrode the content host liability under the Classification

Act. - The Amendment makes important changes to the existing Classification Act and its application, including:

- Adding “sound” to the categories of publication covered by the Act.

- Adding the livestreaming of objectionable content as an offence, punishable by 14 years of imprisonment for an

individual and a fine of up to about $136,000[8] for a corporate body. The

provisions on livestreaming also prohibit the sharing of duplicates of the livestream (including sound and

images) and of information enabling access to the livestream in the knowledge that the content is objectionable

or has “the intent of promoting or encouraging criminal acts or acts of terrorism.” - Removal of safe harbour protection guaranteed under the HDCA for content considered objectionable under the

Classification Act. However, service providers’ exemption from legal liability remains for platforms on which

objectionable content has been livestreamed. Platforms also retain their exemption from criminal and civil

liability if they comply with a takedown notice. - New powers for the Chief Censor to issue an “interim classification” if the content is likely to be

objectionable. This is limited to instances where the Chief Censor believes it urgently necessary to make the

public aware that a publication may be objectionable and likely to cause harm. - An immunity from civil suits for officials undertaking classification in “good faith, including for

“interim classification”. A similar immunity exists for platforms removing content in response to a takedown

notice or to an interim classification. - Part 7A of the Amendment relates to takedown notices, which apply to any content accessible in New Zealand.[9] Takedown notices can be issued by an Inspector of Publications[10]

provided that: - An interim classification has been made;

- The content has been classified as objectionable;

- “The Inspector believes, on reasonable grounds, that the online publication is objectionable.”

- The Amendment specifies that service providers are required to comply with takedown notices: “as soon as is

reasonably practicable after receipt of the notice but no later than the end of the required period – the

Amendment does not specify the “required period” but notes that the Inspector “must consider what period is

likely to be reasonably practicable for the online content host to comply with the notice.” - If a platform fails or refuses to remove a piece of content, an Inspector may commence enforcement proceedings

in the District Court. In which cases, the Court may order compliance with the takedown notice and/or financial

penalties. Fines can be up to about $136,000[11], and the Court is to take into

account the nature and extent of the failure or refusal to comply with the takedown notice. Only one fine may be

issued per takedown notice. - The Amendment states that the Secretary of Internal Affairs must make public a list of all takedown notices

issued and complied with, as well as publish metrics on takedown notices in an annual report to the DIA. When

compiling a public list of takedown notices, the DIA must also provide the reasons for the takedown.

The Classification Act

- The Classification Act stipulates that the making, distribution, and viewing of content considered illegal or

“objectionable” constitutes an offence in New Zealand. - The Classification Act defines “objectionable” content as a publication that “describes, depicts, expresses, or

otherwise deals with matters such as sex, horror, crime, cruelty, or violence in such a manner that the

availability of the publication is likely to be injurious to the public good.” The Classification Act includes

an explicit prohibition of child sexual abuse material and content that depicts torture or extreme violence. - Amongst the different factors to be considered when assessing content is whether it “promotes or

encourages criminal acts or acts of terrorism”, or “represents (whether directly or by implication) that

members of any particular class of the public are inherently inferior to other members of the public by reason

of any characteristic of members of that class, […]”. Both terrorism and hate crimes are thus considered

objectionable. - Under the Classification Act, content downloaded or accessed from the internet (“Internet-sourced publications”)

is subject to classification when the relevant action takes place New Zealand. The Classification Act also

has jurisdiction over websites “operated or updated from New Zealand.” If someone in New Zealand uploads

objectionable content to a website hosted overseas, they can be prosecuted under the Classification Act for

having made the content available in New Zealand. - The Classification Office also specifies that chat logs and chat rooms are subject to New Zealand law and

can be monitored by the DIA if concerns are raised.[12]

Harmful Digital Communications Act, 2015

- Art. 22 of the HDCA states that it is an offence for a person to post a digital communication with the intention

of causing harm. This offence is punishable by up to 2 years imprisonment and a $50,00 fine for an individual or

a $200,00 fine for a corporate body. - Art. 23 guarantees a platform’s exemption from legal liability for user-generated content, as long as the

platform is in compliance with the process outlined in Art. 24. As such, in order to obtain an exemption from

liability for specific content a platform must: - Notify the author of the published material within 48 hours that a complaint has been made regarding their

content; - If the platform is unable to contact the author, the platform must take down or disable the content within the

same 48 hours, whilst also notifying the author of their entitlement to file a counter-notice within 48 hours of

the original complaint.

Tech Against Terrorism’s Analysis and Commentary:

Commendable shift in avoiding automated content filters

The first version of the Urgent Interim Classification of Publication and Prevention of Online Harm Amendment introduced provisions establishing an electronic system to prevent access to objectionable online publications which would have been administered by the DIA. In practice, this electronic system would have acted as an automated filter monitoring all online content in New Zealand.

However, this was met with widespread opposition. All parties in the New Zealand Parliament, with the exception of the governing party (Labour) which had proposed the law, voted against the first reading of the bill in opposition to the filtering system. Technical experts and digital right advocates had also advised the government against the filter,[13] a perspective shared by David Shanks, New Zealand’s Chief Censor, who raised concerns about the lack of safeguards for human rights.[14] Many criticisms of the filtering system concerned the bill’s lack of detail about how the system would function in practice and about the Department of Internal Affairs administering it. The second point concerned the regulation of prohibited content in New Zealand, in that the DIA would have been able to directly block access to a website or content via the filtering system – whereas classification of a content as objectionable is entrusted to the independent Classification Office as per the Classification Act.

The removal of the provisions for a filtering system, which is reminiscent of the attempt by the Government of Mauritius to establish a proxy-server to screen all internet traffic in the country to detect illegal or harmful content, is commendable. Filtering systems and the systematic screening of all online content threaten online freedom of expression with the risk that legal and non-harmful speech will be removed.[15] Tech Against Terrorism detailed the challenges and risks for fundamental rights presented by the use of filters in our Online Regulation Series Handbook.[16]

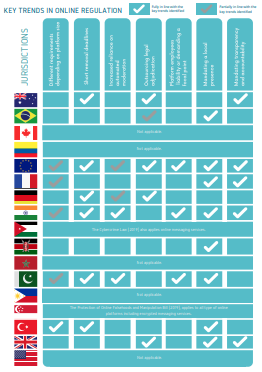

A step-away from key trends in online regulations

The Urgent Interim Classification of Publication and Prevention of Online Harm Amendment does make certain significant changes to the New Zealand regulatory online framework. Most notably, it establishes platforms’ liability for failing to act on takedown notices, and grants more enforcement power to Inspectors of Publications and the Classification Office. However, the Amendment remains anchored in New Zealand’s pre-existing framework for prohibited content.

As such, New Zealand’s updated online regulatory framework deviates from the regulatory trends identified by Tech Against Terrorism in the Online Regulation Series Handbook. Instead, New Zealand refrains from mandating automated filters, as explained above, and from delegating legal adjudication to tech platforms - the burden of assessing whether content is objectionable remains with the state, in the form of the Classification Office.

The requirement for platforms to rapidly remove objectionable content following a takedown notice is one exception, as it would align New Zealand with the regulatory trend of setting short removal deadline.[17] However, the Amendment requires the Publication Officer to account for what is “reasonably practicable” to expect from a platform in setting a removal deadline. Tech Against Terrorism recommends that the Secretary of Internal Affairs, which oversees the Officers, to build up on this specification and establish a grid for the setting of removal deadline that fully accounts for the limited resources and capacity of smaller and newer platforms.

“Intent of promoting terrorism”

Whilst the 2021 Amendment is anchored in New Zealand’s existing legislation on objectionable content, the provision prohibiting information on how to access a livestream of objectionable content may warrant some safeguards for journalists and researchers.

Objectionable content, including terrorist and violent extremist material, is of value for journalists and for researchers investigating specific acts of terrorism or violence and/or researching on trends in terrorist use of the internet. Tech Against Terrorism recommends New Zealand policymakers to include caveat to ensure that individuals with a legitimate reason to access objectionable content will not be penalised under the Amendment.

[1] 10 tech companies and more than 50 governments have supported the call since its launch, in addition to the 50+ civil society, counterterrorism and digital rights experts who have joined the Christchurch Call Advisory Network.

Tech Against Terrorism is proud to be a member of the Advisory Network and has supported the Christchurch Call since its inception. On the Second Anniversary of the Christchurch Call to Action in May 2021, we announced an expansion of the Terrorist Content Analytics Platform’s (TCAP) Inclusion Policy to cover material produced by the Christchurch attacker, who was designated as a terrorist by New Zealand in 2020. The TCAP now notifies tech companies of material directly produced by the attacker, including the manifesto and duplicates of the livestream of the attack. In cases where content is either a direct translation, or an audio version of the manifesto, we also alert tech companies.

See: Terrorist Content Analytics Platform (2021), TCAP Support for the Christchurch Call to Action.

[2] amendment to the Films, Videos and Publications Classification Act of 1993

[3] Khandelwal Kashish (2021), New Zealand passes counter-terrorism law following Auckland supermarket attack, Jurist.org

[4] Baigent Jania and Ngan Karen (2015), Harmful Digital Communications Act: what you need to know, Simpson Grierson.

[5] The Bill was introduced in Parliament in May 2020 and received Royal Assent on 2 November 2021. The Act is to come into force on 1 February 2022.See: Scoop.co.nz (2021), New Tools To Deal With Harmful Illegal Material Online.

[6] Other online issues, such as online bullying, discrimination or racism can be reported via the dedicated platform: Report harmful content Netsafe.

[7] https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/BU2112/S00065/nzs-draft-code-of-practice-for-online-safety-and-harms-now-available-for-feedback.htm

[8] 200,00 New Zealand dollars

[9] “individuals in New Zealand (the public) and service providers in New Zealand as well as online content hosts both in New Zealand and overseas that provide services to the public.”

[10] Inspectors of Publication are appointed by the Secretary of Internal Affairs as per the Classification Act.

[11] 200,00 New Zealand dollars

[12] https://www.classificationoffice.govt.nz/about-nz-classification/classification-and-the-internet/

[13] Daalder Marc (2021a), Scrap internet filters, select committee told, Newsroom.nz

[14] Daalder Marc (2021b), Internet censorship provisions to be scrapped, Newsroom.nz

[15] EDRi (2018), Upload filters endanger freedom of expression.

[16] We underline in particular that the use of automated solutions to detect and remove terrorist content is not necessarily straightforward, as these solutions cannot replace consensus on what constitutes a terrorist organisation and need to be informed and adjusted responsibly by governments and intergovernmental organisations. See section on Key Trends in Online Regulation, pp.17 – 29.

[17] Short deadlines to remove prohibited content, including terrorist material, and to comply with takedown notices, have been passed in the EU, Australia, Germany, India, and Pakistan.

- News (240)

- Counterterrorism (54)

- Analysis (52)

- Terrorism (39)

- Online Regulation (38)

- Violent Extremist (36)

- Regulation (33)

- Tech Responses (33)

- Europe (31)

- Government Regulation (27)

- Academia (25)

- GIFCT (22)

- UK (22)

- Press Release (21)

- Reports (21)

- US (20)

- USA (19)

- Guides (17)

- Law (16)

- UN (15)

- Asia (11)

- ISIS (11)

- Workshop (11)

- Presentation (10)

- MENA (9)

- Fintech (6)

- Threat Intelligence (5)

- Webinar (5)

- Propaganda (3)

- Region (3)

- Submissions (3)

- Generative AI (1)

- Op-ed (1)